For years, I’ve sat with HR teams in global corporations to understand how they use data. This is the work of organizational ethnography: not just looking at the org chart, but observing what people actually do. When I ask an analyst how they get the information they need to answer a critical business question, they rarely show me a dashboard.

Instead, they tell me a story.

It’s a story about "walking the square", a winding, almost ritualistic journey from one person to the next.

"First," they'll say, "I have to email Susan in Comp, because she's the only one who knows how to pull the bonus data. Her system doesn't talk to the main HRIS. Then, I take her spreadsheet and send it to Raj in Talent, who has the master list of high-potentials, which he keeps in a separate file because he doesn't trust the performance module. Then I have to..."

This story is not an exception. It is the norm.

The "Human API" as Organizational Glue

These people, Susan and Raj, are what I affectionately call "human APIs." They are the living, breathing, and completely overburdened interfaces for critical business data. They are the unofficial governance, the unwritten rulebook and in some cases, the main highway for data movement.

We focus endlessly on system architecture and technical APIs, but the most powerful systems in any company are the human systems, the networks of trust, obligation, and informal knowledge that dictate how work actually gets done. In many organizations, these human systems are in many cases the only things holding a fragmented data landscape together.

This "human API" doesn't just pass data and I’m not here to just pass judgement. They perform three critical functions that our technology has failed to:

- They Gatekeep: Not a pejorative here. They know who should and shouldn't have access, based on social capital and internal politics, not a clear set of rules.

- They Translate: They know that "Termination Date" in their system means "last day worked," while in the payroll system it means "last day paid." They manually fix this.

- They Validate: They are trusted. When Susan sends the file, the analyst knows it's correct because "Susan knows her stuff." She has vouched for it with her personal reputation.

This entire ecosystem is built on personal relationships. It is artisanal, non-scalable, and creates massive bottlenecks. When Susan goes on vacation, a part of the company's data infrastructure effectively "goes down."

The Real Labyrinth: A Culture of Mistrust

This reliance on human APIs is a reality for many teams out there, but not a long term solution. It is the symptom of a much deeper, more complex cultural labyrinth. This is a world away from the clean org charts of "data governance" councils and "stewardship" roles. The lived reality of data is a mess of competing incentives, hidden fears, and social rules.

When you map this human system, you find the real barriers to transformation are not technological. They are cultural.

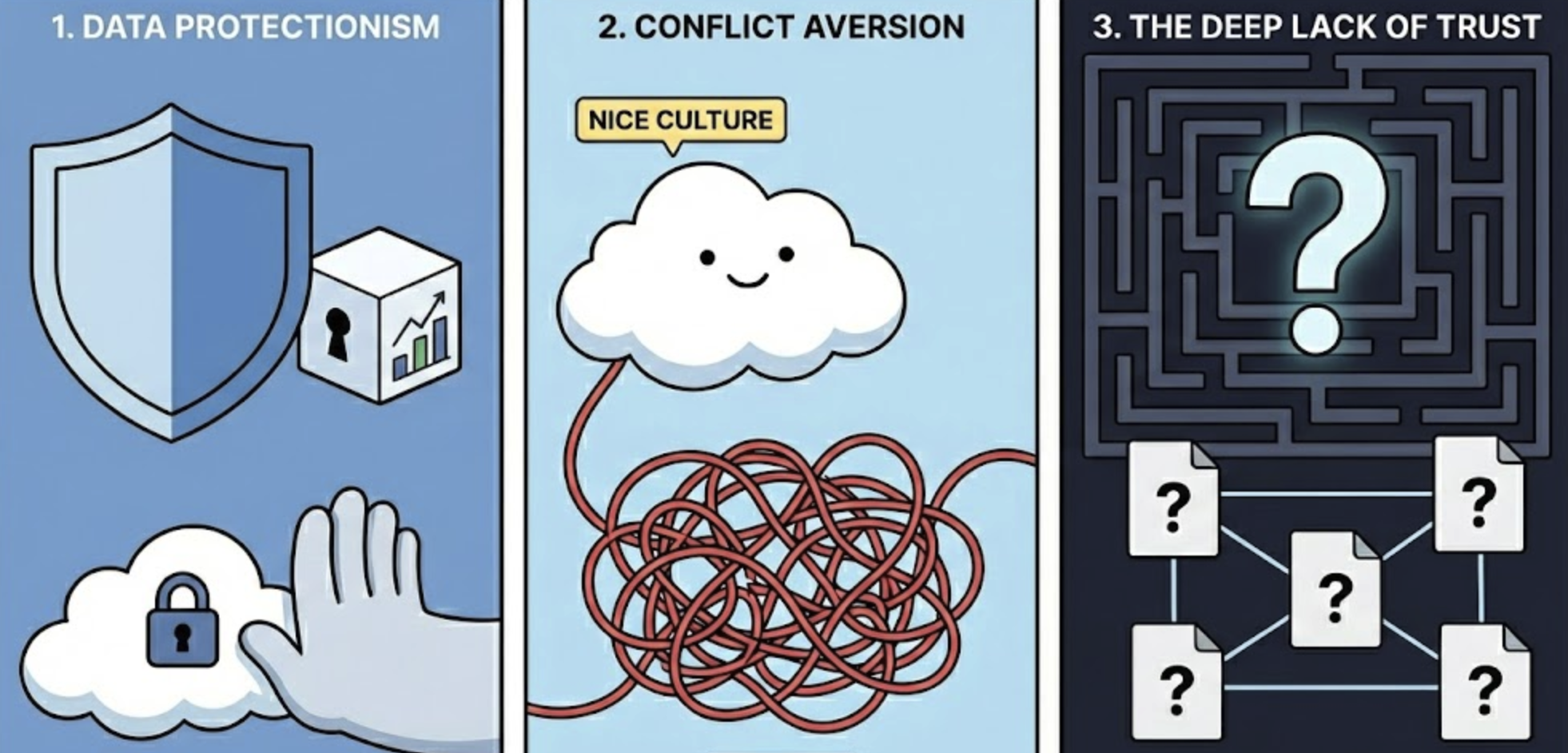

1. Data Protectionism (Data as Identity)

In many organizations, data isn't just data; it's a reflection of performance. A manager's "turnover rate" or "engagement score" is tied directly to their identity as a leader. We see Data Protectionism, where managers "protect" their team's data, not for security, but because bad or out-of-context data might make them in turn look bad.

Not to defend it as this isn’t great for anyone when it happens, but it isn't irrational. It's a perfectly rational, local, response to a culture that punishes leaders for bad numbers without understanding the context. The "human API" (like a finance partner or HRBP) acts as a shield, ensuring no data leaves their silo until it has been "blessed" and "contextualized."

2. Conflict Aversion (The "Nice" Culture)

We see a "Nice" Culture that avoids the direct, healthy conflict required to fix systemic issues. In this environment, telling a functional leader that their data is unusable is a grave organizational sin. It breaks the illusion of harmony.

So what happens? People create workarounds. The analyst "walking the square" is performing a conflict-avoidance ritual. Instead of confronting the source of the bad data, they spend 20 hours a month manually cleaning spreadsheets. This preserves the social relationship at the cost of systemic automation.

3. The Deep Lack of Trust (The "Shadow Ecosystem")

The result of the first two points is the real problem which is an unavoidable and deep, corrosive Lack of Trust. Every "official" dashboard is second-guessed. Every corporate report is manually re-validated.

This gives rise to a "shadow analytics" ecosystem. Every leader has their own "version of the truth" in a spreadsheet. Meetings devolve into battles of dueling spreadsheets, with everyone arguing about whose numbers are "right." The expensive, official BI tool sits unused because everyone knows, deep down, that the source data is flawed.

The Seduction of the Technical Fix

Technology investment alone is a great idea, but cannot fix this without an additional reset on the cultural elements. This is the central fallacy of most data transformations.

A new, billion-dollar AI-ready enterprise IT push won't solve data protectionism; the manager will still refuse to put their "real" data into it. A new dashboard won't fix a lack of trust; leaders will still export the data to Excel to "check it" against their own shadow system.

We buy new technology because it's a clean, tangible, budgetable project. It's far easier than the "messy" work of changing human behavior and incentives. But the result is always the same: the technology fails. The human system simply rejects it, like a body rejecting an implant, and the old "human APIs" and shadow spreadsheets live on.

The Sociotechnical Work: Your Path Through the Labyrinth

This is sociotechnical work. It's a discipline that treats technology and social structure as a single, intertwined system. You cannot change one without fundamentally changing the other.

Buying a new platform is easy. That’s just a technical fix. The real work, the sociotechnical work, is redesigning the human systems of trust, incentives, and power that govern your organization. This is where HR differentiates and breaks out of IT roles. It means asking the hard questions:

- How do we build systemic trust? How do we move from "I trust Susan's spreadsheet" to "I trust the platform," by proving the platform's data is more reliable, transparent, and contextualized than Susan's manual efforts?

- What incentives are we changing? If we want managers to stop protectionism, we must create a culture where data is a tool for diagnosis and support, not a weapon for judgment.

- How do we replace social capital? How do we replace the "who you know" access of a "human API" with a formal, fair, and fast process, like the "data warrant," that runs on rules, not relationships?

This is where most transformations fail. They buy the new AI tool but ignore the human labyrinth it's about to enter. The technology is rejected, the "human APIs" remain the bottlenecks, and millions are wasted.

Before you buy the next platform, ask yourself: Do you truly understand the human experience of this data labyrinth you are transforming?

Your Guide Through the Labyrinth

At Ikona Analytics, we are not just technologists; we are organizational guides and sociotechnical architects. Our work begins before the technical implementation. We embed with HR and IT teams to map that human labyrinth.

We sit with your analysts, your managers, and your "Susan-and-Raj" human APIs to understand the real workflows, the hidden fears, and the cultural blockers. We help you redesign the human systems of trust, incentives, and governance alongside the technical architecture.

This sociotechnical approach is the only way to ensure your data transformation actually transforms, that your investment sticks, your people adopt the new tools, and your AI ambitions are built on a foundation of rock, not mud.

If you're an executive who is tired of funding data projects that fail to change behavior, let's talk. If you recognize the "human APIs" and "shadow ecosystems" in your own company, you don't just have a technology problem.

You have a human-systems challenge. We are the guides for that journey.

.png)